The long period of the Middle Ages, which stretched from the end of Antiquity to the beginning of the Renaissance, was marked by the domination of one school of thought: the Christian religion. This religion unified over the course of the centuries, accepting the authority of the Pope. It permeated every level of society, from the bottom to the top of the social scale; governed the lives of individuals; and was ever-increasingly firm at imposing its dogmas, i.e. Its fundamental, indisputable and intangible affirmations..

The notion of heresy re-emerged at the end of the 9th Century. The year 1000 was haunted by the combat between good and evil: under the banner of the Pope, holy war was justified, against infidels or heretics.

In a person's daily life, this spirituality manifested as a permanent concern as to whether one's sins would be forgiven, and whether one’s soul would find salvation after death. In their quest for pardon, people, whether rich or poor, were guided by the Church. Sacraments, pilgrimages, donations and devotion to the relics of saints were just some of the ways in which you could express your faith. For a noble during the Middle Ages, there was a real benefit in being buried close to the relics of a saint or making donations to an abbey. For anyone, pilgrimage is one path towards forgiveness.

Alongside the secular clergy, like bishops and priests, who lived amongst the people in order to guide the faithful, the regular clergy prayed for everyone. This clergy was the monks, who lived a life governed by a Rule. Numerous rules have been drawn up since Antiquity, but one has come to dominate the Western Christian world: the Benedictine Rule.

In the 12th Century, the Church became rich and powerful, and was dotted with various movements seeking a return to the ideal of poverty. Numerous orders arose and it sometimes took time before they were accepted by the papacy, as was the case for the Franciscans, for example. The period also saw the emergence of what the Church would refer to as “heresies”, i.e. schools of thought in contradiction with dogma. Catharism was one of these schools.

The Rule of Saint Benedict

Written in the 6th Century by Benedict of Nursia, the Benedictine Rule was taken up again in the 9th Century by Benedict of Aniane. This monk, born in Septimanie, near Montpellier, was a close advisor to the son of Charlemagne, Louis the Pious. Its reform aimed to organise the life of the monks around prayer, work... and the glory of Carolingian power. Under his influence, the foundation of abbeys multiplied to the very edge of the Empire, with abbots at their head who were often close to royal or seigneurial power. Whereas monks towards the end of Antiquity travelled all across Europe to preach the Gospel, the monks of the Middle Ages cut themselves off from the world in monasteries, where they lived as a community. These richly endowed monasteries became veritable economic lungs and ended up drawing in populations, to become villages and sometimes even towns. Some Rules had existed since Antiquity and yet others would be created subsequently, but none became as widespread or influential as the Benedictine Rule.

Catharism

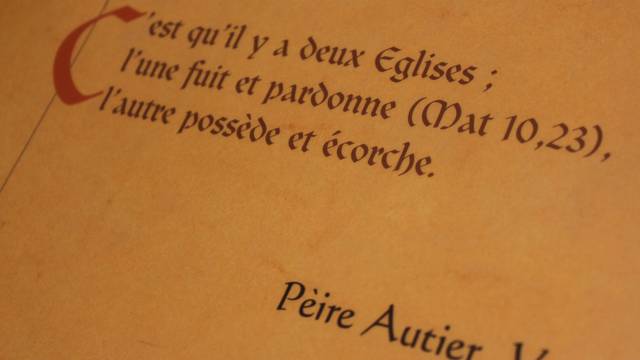

Occitanian Catharism was composed of a series of independent churches that maintained friendly relations with each other. The Cathar Church was composed of the faithful and a clergy of Perfect men and women, administered by bishops and deacons. Cathar communities lived according to certain rules: poverty, chastity, vegetarianism and physical labour. The Perfect men and women, who lived in houses or workshops, remained in contact with the people. They visited families to bless the bread at dinner or preach, and people were allowed to come and talk to them. They opposed Catholics by virtue of their dualism. In their view, this fleshly world was the work of the Devil, and souls were locked into “skin tunics”. Christ, who had come to deliver them, was not made man and was therefore not present at the Eucharist. They recognised only one sacrament, consolamentum, which performed the functions of marriage, extreme unction, baptism and more. However, for historians, Catharism remains a controversial topic, as not all researchers interpret the contents and meaning of this religious movement in the same manner.

St. Dominic and the Order of Preachers

At the end of the 12th Century, Dominique de Guzman, who would later become St. Dominic, intervened in Languedoc at the request of Pope Innocent III to fight against Catharism, which had been declared heresy. The Cistercians, led by St. Bernard, had already come to preach...in vain. To combat the influence of the Cathars, Dominique founded the monastery of Prouilhe in 1206, near Fanjeaux, where there were a large number of Cathar communities; this was the first monastery created for Dominican women. He participated in the theological debate of Montréal, where he argued against Benoît de Termes, the Cathar bishop of Razès. But the crusade seemed inevitable, and persuasion gave way to arms. Dominique, however, continued to believe in conversion. He founded the Order of the Preachers, better known as the Dominicans. These monks, who follow the rule of St. Augustine, were encouraged to learn how to counter heretical theses.

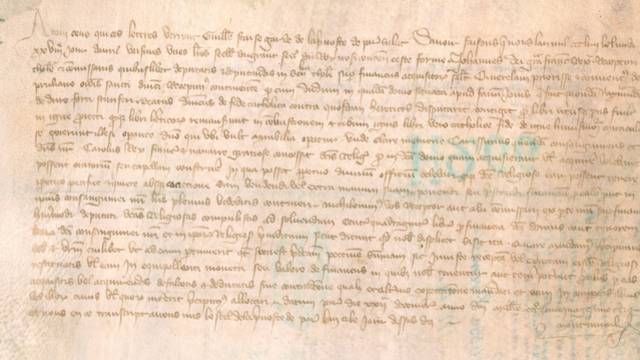

The Inquisition

Languedoc was under the military dominion of the King of France, but the Cathar heresy had not been stamped out. The Inquisition, founded in Languedoc in 1233, was entrusted by the Pope to the Order of Preachers; its mission was to extirpate Evil, and it had total authority. Inquisitors were confessors, investigators and judges all at once. Penitents were absolved if they confessed their crimes and recounted everything they knew. Those confessions were then used to trace the spread of movements and dismantle them. The inquisitorial prison erected in Carcassonne, not far from the Old Town, was known as The Wall: people entered, but they did not come out. An Inquisitor never acted as executioner, however: the secular arm was always responsible for carrying out the death sentences pronounced against those who refused to confess...The last Cathar dignitaries were sent to the stake just over a century after the onset of the Albigensian Crusade: Pèire Autièr in Toulouse in 1310, and Guilhem Bélibaste in Villerouge-Termenès in 1321. The last known remaining believers were burned in Carcassonne between 1325 and 1330.