During the 10th Century, life became more difficult for those without arms, i.e. peasants and the clergy. It was the feudal period, and the seigneurial lords’ exercise of their power over the people was violent. Society had become stateless. The Comtes were feudal lords who operated independently of the power of the Crown. They became suzerains: their vassals derived their dominions from their hands. They swore to defend their interests, sword in hand.

At the same period, from the 11th Century onwards, châteaux were beginning to proliferate. They become the beating hearts of seigneurial power. These châteaux, initially somewhat intimidating for the common people, ended up in the 12th Century becoming sources of protection as well as of the restrictions imposed by seigneurial power. It was at this period that a large number of villages tended to emerge around châteaux.

And the Church? The Church strove to play an important role in pacifying the regions by imposing the Peace of God, in an effort to limit the more violent abuses from the knights. In another crucial initiative, the Church launched the “Gregorian Reform“ in the 12th Century to guarantee its independence from any lay powers.

In the Pays d’Oc region, three main hubs remained in conflict with each other throughout this period: Poitiers, Toulouse and Barcelona. The opposition between Toulouse and Barcelona came to a head in the “Great Southern War” during the 12th Century.

There is one viscountry between Toulouse and Barcelona of particular interest to us: the viscounts of Trencavel, lords of Albi, Carcassonne-Béziers and the Razès region. The Trencavels’ allegiance was flexible, with them going from being allies of Barcelona to defenders of the Toulousain heartland...They were successful in holding onto their principality until the arrival of the crusaders in the 13th Century.

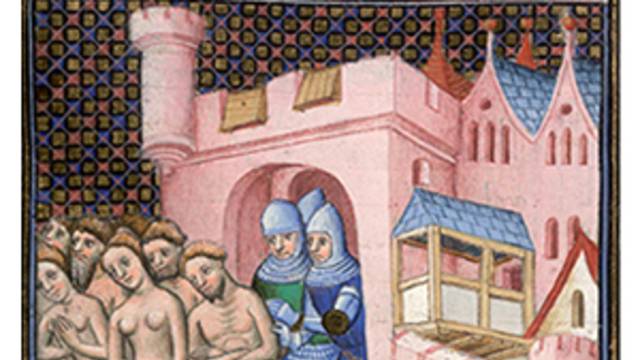

The crusaders did not have much trouble overcoming a region that was already weakened and was fractured on a political level. The new Capetian rulers ended up establishing a new administrative and judicial order, founded on senechalsies, which acts as seats of the royal power.

Comtal power

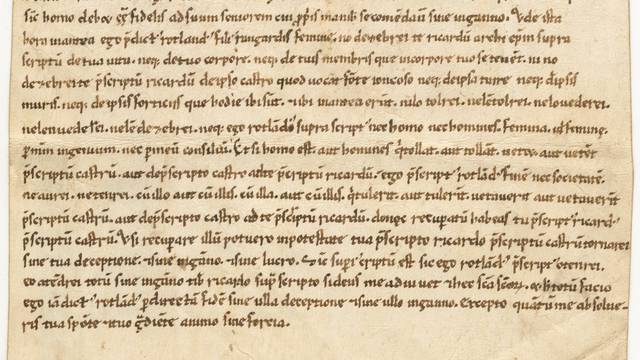

In the 10th Century, comtal power was a family affair: rights and privileges were shared around by an entire dynasty. This is not to say there were not disputes over inheritances, disagreements on both sides and, finally, confrontations. In the 11th Century, comtal power proved unable to maintain order, and was forced to seek out new alliances. Within comtal families, vows of non-aggression were concluded: “Thou shalt not harm my life nor my possessions (cities, counties, bishoprics, châteaux, etc.), but there shall be no relationship of subordination between us.” Another type of vow emerged in ever-increasing numbers: the feudal vow. These vows were attached to one château in particular and recognised a superior power vested in the suzerain lord, whose vassal the person making the vow then became. In practice, however, that vassal became the effective lord of the manor.

Power and the Church

Between the 8th and 9th Centuries, Benedict of Aniane reformed the Benedictine Rule. At his initiative, the kingdom covered itself in monasteries singing the praises of the Carolingian rulers. Some abbots were friends of Benedict of Aniane himself, such as Nimfridus, first abbot of Lagrasse. During the 10th Century, royal power could no longer be exercised on boarder regions that were too far away. It was a time of feudalism, and a time when violence was endemic. Abbots and bishops were themselves lords of the manor, with numerous villages under their authority. The new military caste of knights wasted no time in asserting their rights. The Church reacted by imposing the Peace of God in an attempt to pacify the Christian world and consolidate its possessions. Finally, in the 12th Century, the Church launched the Gregorian Reform. It proclaimed its independence from any civil authority, asserted the Pope's predominant position and undertook a reform of the clergy...Its power grew on both a spiritual and a material level.

From the Great Southern War to the Albigensian Crusade

The Great Southern War that raged in the Midi region of France for a large part of the 12th Century pitted two major counties against each other: Toulouse and Barcelona. This conflict at a European scale, in which the Kings of England were also involved, was very complex. Allegiances were made and broken. In Carcassonne, the Vicomtes Trencavel were vassals of both the Comtes de Toulouse and the Comtes de Barcelona. In 1177, the Comte de Toulouse sought to undermine Trencavel, whose possessions were located between Toulousain and Provence. He denounced the extension of heresy in Midi to the General Chapter of Cîteaux. This act, which attributed this territory to the partisans of the Crusade, had serious consequences. A peace between Southerners was signed in Perpignan in 1198, but it was overdue and ambiguous. In 1209, at the onset of the Crusade, the Comte de Toulouse himself came to the ramparts of Carcassonne to lay siege to his own nephew Trencavel...

Royal peace

Keeping the peace and the image that people had of him were a priority for Louis IX. The end of the Albigensian Crusade in 1229 marked the incorporation of part of the Midi counties under the French Crown. The King was thus responsible for enforcing peace both within France and abroad. The senechalsy of Carcassonne was set up in 1226: the army, justice, administration and taxes were in the hands of the seneschal, himself a representative of the King. Relations between the King and the local feudal lords, some of whom were former crusaders, needed to be pacified, even if that meant thwarting the Inquisition. Security also needed to be maintained against Aragon. The Treaty of Corbeil in 1258 created a common border south of Corbières between France and Aragon, and created two “march-borders” that needed to be guarded. On the Capetian side, the seneschal of Carcassonne was placed in charge of implementing the King’s ambitious projects. Termes, Peyrepertuse, Quéribus, Puilaurens and Aguilar to the south and Lastours, north of Carcassonne, were fortresses via which he intended to reassert his power and prestige.