The Pays d’Oc region was not united by its politics in the Middle Ages, but rather by its culture and its language. In this region of southern Europe, which goes from the Atlantic to the Alps and from the north of the Massif Central to the Pyrenees, people spoke the language of Oc, or more precisely, the different dialects that come from the Occitan language. This Romance language was the language of troubadours and literary creation, and, together with Latin, that of the notaries and communal administrations. This lasted until French began to take hold, first of all in written language, at the beginning of the 16th Century, via the prestige of the French monarchy.

The Middle Ages saw the economic and cultural explosion of Europe. Here, as everywhere, towns and the urban elite were developing. The countryside and peasantry were also growing. Romanesque and Gothic art give birth to masterpieces of architecture, sculpture, painting and even music. Under the all-powerful leadership of the Roman Church...

In terms of politics, two great powers clashed in Occitanie: the counts of Toulouse and the Catalan counts. But this principle antagonism was actually a multiplicity of alliances and rivalries, between two vassal lords or more, and sometimes all of them at once... conflicts were numerous, long and complex.

The Albigensian Crusade would put an end to this dissension. The Crusade, initially waged for religious reasons, became the defining event n the mediaeval history of this region, not only for its violence but also for its political impact: a border began to emerge at the South, a border for the kingdom of France.

Troubadours invent the art of the “trobar”

The “canso” was a song in verses, a form of lyric poetry that emerged in the 12th Century among poets versed in the art of trobar, leaving Latin behind and preferring to adopt the Occitan language, which they initially called “roman”. Those who enjoyed the trobar or troubadours, such as Pèire Vidal in Saissac, composed and sang these poems, mainly about ”fin’ amor” (or courtly love) in the Occitanie courts and further afield. Their works, adopted by travelling musicians, arrived in the principalities of the North of France during the 13th Century, where other poets, the trouvères, drew inspiration from them to sing legends such as the legend of King Arthur, and in turn invented a new form: the roman. The instruments of the troubadours and those who played them, the jugglers or ‘joglars’, have been recreated by archeomusicologists and can be seen and heart in Puivert.

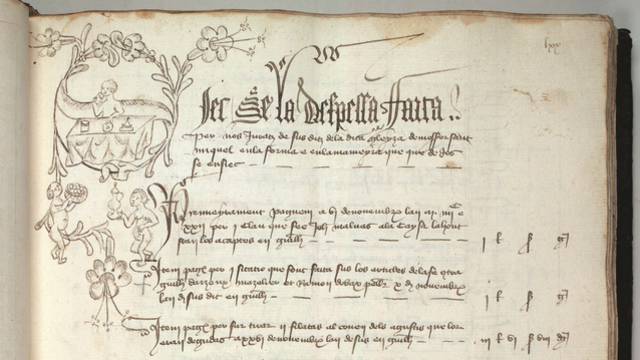

A culture of writing

The Pays d’Oc was a region of written law, where Roman law had been reintroduced from Italy during the 12th Century. This use of written texts in the legal field was unique to the Occitanian South. Thus, the use of the vernacular, or the spoken language, is recorded in treaties, vows, wills and testaments, administrative documents and more. In Lagrasse and Limoux, for example, there are registers of the consuls of the 14th and 15th Centuries written in Occitan. Moreover, by association with the troubadours’ literary activity, the oldest treaty on grammar for Romance languages was probably written in the mid-13th Century by an Occitanian, albeit intended for an Italian readership.

Artistic movements throughout Europe

In the 11th -12th Centuries, Romanesque art reigned. The Master of Cabestany, sculptor of the movement and the story, created masterpieces such as the altar front at Saint-Hilaire, and the capitals at Saint-Papoul. Gothic art developed in Europe from the 13th century. The pursuit of light was in fashion, as magnificently illustrated by the abbey church of Lagrasse. Southern European Gothic was well represented in several churches in the region, a rather austere architecture born in the wake of the Crusade against the Albigensians. A colourful, joyous and sophisticated art was also seen at the end of the Middle Ages: painted ceilings. This art, still largely unknown today, has been the subject of recent research. It can be found in some opulent houses in town. The ceilings are both grotesque and refined, insolent and a sign of notability.

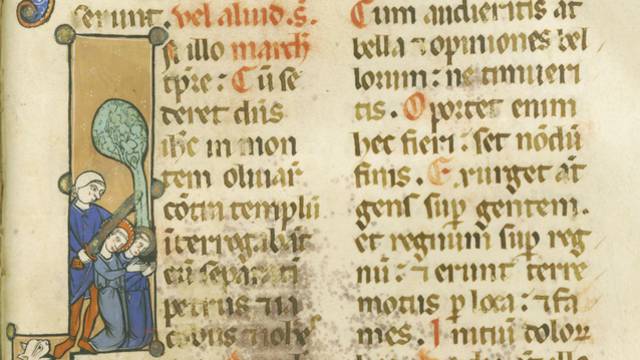

A religious society

Mediaeval society was more than anything religious, specifically Christian. Very early on, the lay feudal lords relied on the bishops and monks to consolidate their power. Very early on, the line between lay and religious authority blurred: the same families governed the whole of society. However, faith was genuine and was felt to be fundamental. Whether you were a lord of the manor or a peasant, you focused your life on one goal: avoiding Hell and going to Heaven. To achieve that, you obeyed, and when you were rich, you made donations - to abbeys, to churches and to the poor. Legends, saints, miracles, relics and so on all lent depth and legitimacy to authority. St. Hilaire watched over the Comtes de Carcassonne; St. Gauderic granted bountiful crops to farmers in Lauragais; and Christ himself was present for the foundation of Lagrasse.

A flourishing economy

Land was being cultivated, the forests cut back, and villages were built around churches or châteaux, especially during the 11th and 12th centuries.

The former mound of Prouilhe, overlooked by Fanjeaux, bears a windmill dating from the early 13th Century. It is the oldest trace of this type of building in the whole region.

The rivers’ courses were developed by water mills. Mills were used to grind cereals and process fabric, as was done in several mills attached to the Templar preceptory in Douzens. The textile trade was very important and widely found in the Cathar workshops. They were nicknamed the ‘tisserands’, or weavers. The other source of wealth was mining. The Corbières and the Montagne Noire mountain ranges house silver and iron mines that had been operated since Antiquity. The goods were moved around and exchanged at very lucrative fairs and markets.